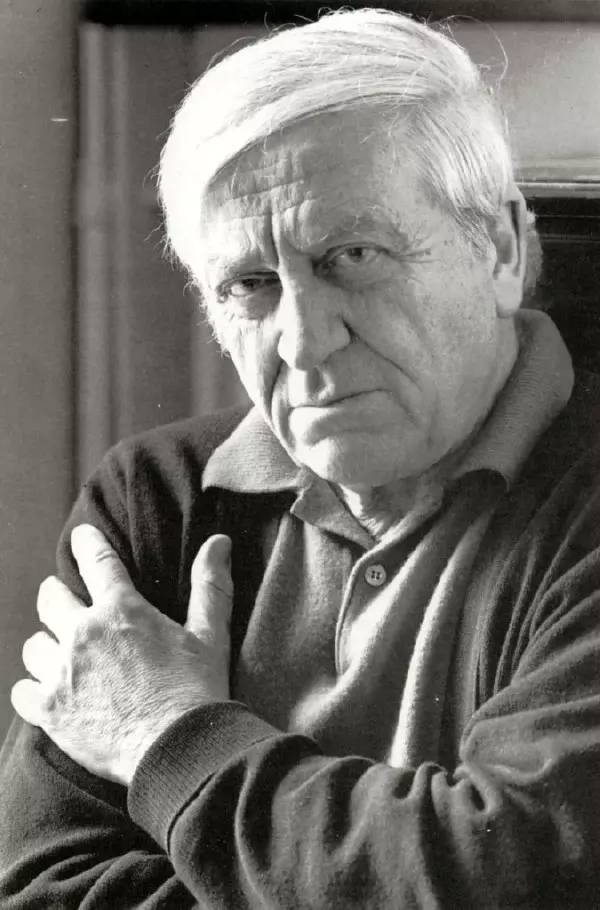

莫里斯·奥阿纳,Ohana Maurice

继德彪西、梅西安、里盖蒂之后,奥阿纳是对音乐语汇进行创新的又一代表性的现代作曲家之一。

莫里斯·奥阿纳(Maurice Ohana,1913—1992)西班牙裔法国作曲家,是 二十世纪下半叶法国乃至欧洲最具代表性的作曲家之一,他出生在法国一个具有西班牙血统的家庭,随父亲继承了英国公民的身份,并在1976 年加入法国籍。与当时一批西班牙音乐家、艺术家和作家一样,他们都向北移居到法国,运用他们传承下来的文化传统进行创作。

奥阿纳很小就显露音乐的天赋,l1 岁时就举行了钢琴音乐会,18 就公开演奏了贝多芬全部32 首钢琴奏鸣曲。青年时期,奥阿纳在摩洛哥、西班牙和巴斯克地区游历,所以很早就熟悉西班牙民歌。他从母亲那里学习了许多西班牙的小说和舞蹈,同时也学到了许多英雄史诗以及萨苏埃拉(zarzuela)。正是奥阿纳身处这样复杂而不寻常的文化渊源,使得他能够超越国家政治边界的意义而直接吸收各国的文化。因此,他的音乐带有显着的地域文化特色。奥阿纳带有异国以及折衷风格一直贯穿着他的创作。奥阿纳作为作曲家,特别是2O世纪6O 年代以后,随着他的音乐成熟时期的定型,他的音乐越来越有着至高无尚的地位。奥阿纳以其鲜明而富有个性化的创作语言,拥有了许多追随者。他的音乐深受德彪西的影响,吸收了包括西班牙民间音乐、爵士、非洲-古巴音乐,中国和日本的戏剧音乐要素,形成了不拘一格的创作风格。

尽管奥阿纳的音乐在当时并没有走上序列主义的道路,也没有加入同时代的达姆斯踏特,更被排除在“新乐天地”之外,但他的音乐却以其鲜明的地域文化特色及异国“折中主义的创作风格”,对法国音乐的发展产生了深远的影响。

1992年去世以后,他的作品一直不断地被大量公演、出版、录音和传播,并出现以“奥阿纳”为名的作曲大赛,以纪念他对二十世纪现代音乐所作出的突出贡献。

奥阿纳的作品几乎涉及了音乐的各种题材和领域,他的作品包括歌剧三部、音乐剧、合唱和大量其他形式的声乐作品、电影音乐、管弦乐、协奏曲、室内乐以及大量独奏作品(包括吉他、钢琴和羽管键琴等)。许多著名指挥家、表演家和演奏家都推崇他的作品,如小泽征尔、阿根蒂尼塔等。直到今天,他的音乐日益为人所知,其创作理论、美学思想和作品不断被整理、挖掘和研究。

莫里斯·奥阿纳的吉他作品

奥阿纳的作品目录及介绍见:http://www.mauriceohana.com/doc/Catalogue_Maurice_Ohana.pdf

在奥阿纳与西班牙吉他大师耶佩斯开始合作以后,他创作和改编了不少吉他作品,并主要都是为十弦吉他而作,包括一部吉他协奏曲《三图协奏曲》(Trois Graphiques,1950–58; 献给Narciso Yepes),两部分别长达30分钟和20分钟的组曲《如果那一天到来(Si le jour parait...)》和《月影(Cadran lunaire)》。此外,也有为六弦吉他创作的独奏曲《恬多曲(TIENTO (no. 31) 》,时长5分45秒,但后来也被改编为十弦吉他演奏。

英文简介:

Maurice Ohana, though born in North Africa in 1913, preferred to claim his birth date as 1914 because of his superstition about the number 13. Of Gibraltarian and Andalusian lineage, he spent his childhood in Morocco, Spain and the Basque region, and studied in both Paris and Barcelona. Ohana throughout his life researched various aspects of flamenco, African and medieval music, and was especially influenced by Debussy and Falla. His compositions include many works for the stage as well as a quantity of orchestral, vocal, chamber and instrumental pieces, and a Concerto, Three Designs for Guitar and Orchestra (1950–57), dedicated to the Spanish guitarist, Narciso Yepes.

Ohana’s guitar music, though indebted to Spanish culture, is far removed from any stereotypical Iberian aspects and, with the exception of Tiento, was written for the ten-string guitar as played by Yepes. Inspired by the possibilities of this newly developed instrument, Ohana’s imagination created an absorbing landscape of profound resonances, allusions and inventiveness. Immense demands are made on both player and listener for the composer’s expectations of the guitar are uniquely his own. Within these works the contemporary developments of twentieth century modernism are fully represented in all their challenging complexity.

The tiento was originally the Spanish version of the toccata, though of a more inward and expressive nature than the customary showy brilliance of the toccata style. It is both a flamenco dance and a feature of the repertoire for the sixteenth-century vihuela, a type of courtly guitar. Ohana’s Tiento (1957) can be described as a work of Spanish allegiance set in a modern idiom. It falls into definite sections beginning with a modernistic statement of La Folia, much loved by composers over the centuries. This leads into rhythmic patterns reminiscent of the habanera and a melodic line which refers to Falla’s Homenaje, Pour le Tombeau de Debussy. A third section hints at a theme from Falla’s Harpsichord Concerto. These ideas are skilfully woven together and the piece ends on a dominant pedal-point with an insistent drum-like beat.

Si le jour paraît…(1963–64) takes its name from Goya’s 71st Capricho, Si amanece vamos (If day breaks, we shall go). By including dots after the title the composer reflects a sense of suspension of action, a hesitation in itself enigmatic. The music includes not only a range of sonorities very different from most guitar pieces but also many innovative techniques.

The seven movements are diverse, some being expressive tone poems, others impressionistic or, in one instance, prompting remembrance of a specific historical event. The overall mood of the composition is sombre, presenting images of introspection and melancholy. The suite is deeply influenced by Debussy’s Préludes, an aspect which extends in the score to placing titles at the end of each movement. Equally significant are implicit elements of flamenco guitar, including rasgueado (strummed chords), clusters of rapid scalic patterns, arpeggiated chords, and the use of percussive devices. Such ingredients, however, are intensely refined and at a considerable distance from the more obvious melodic and rhythmic absorption of Andalusian music in composers such as Albéniz, Falla, Turina or Rodrigo.

The title of the first movement, Temple, according to Caroline Rae, the foremost authority on Ohana’s music, ‘refers to the preparation or tuning-up of a singer’s voice prior to commencing the melismatic improvisations of the Cante jondo ’ (the ‘deep song’ of flamenco). The piece begins with a quasi-improvisatory section leading to a brief episode reminiscent of flamenco’s intricate filigree. This introduces a kind of atonal tango and a subsequent agitated flourish, which brings the movement to a climax. Then the mood quietens until a vibrant coda, marked ‘with the sound of solemn bells’, exploits the ten string’s unique lower sonorities with increasing animation. The piece is dedicated to the guitarist, Alberto Ponce (b. 1935), who edited the suite.

Enueg (or in Catalan enuig) meaning ‘complaint’, was a genre of lyric poetry practised by the troubadours expressing protest and a sense of vexation. This translates into Ohana’s music with an initial explosion of strummed chords played glissandi achieved by sliding a piece of wood, ‘covered or not with thin leather’, up and down. Angular arpeggio figurations, performed ‘metallically’ close to the bridge, tambora, a special drumming effect, and other diversely original sonorities such as percussive sounds on the string with a tuning fork or strip of metal, are also featured.

Maya-Marsya was written in memory of Ramón Montoya (1880–1949), one of the greatest of flamenco guitarists. The opening three-eight tempo and the rhythmic structure, with its repeated notes, present a kind of distillation of the bulerías, the fastest and most exciting of Andalusian forms. But between such episodes, slower, more reflective moods are introduced, including one passage of brilliantly guitaristic scales. In the second half of the work enigmatic strummed dissonances precede a lively coda where the original tempo is transformed into varied patterns of rhythm and syncopation and a final rasgueado effect marked ‘furiously’.

20 Avril (Planh) has been described by Caroline Rae as ‘the expressive heart of the work’. This commemorates the execution on 20 April 1962, of a political prisoner by the Franco régime. Planh (the troubadour’s term for a funeral lament), recalls Miguel Llobet’s guitar arrangement of the Catalan folk-song, Plany (Naxos 8.557351). The work has two predominant textures, the slow opening chords, marked ‘distant, muffled’, and passages of fast demisemiquavers to be played ‘rapidly with violence’, both elements being juxtaposed in the final moments.

La chevelure de Bérénice (Berenice’s Hair) refers both to the constellation known as Coma Berenices and the classical story concerning the hair of Berenice II, the wife of Ptolemy Soter III of Egypt. Berenice had beautiful hair which she offered to present to the goddess Aphrodite if her husband returned safely from war. When Ptolemy returned, she fulfilled her pledge and cut off her hair. Ptolemy visited the temple to look at his wife’s hair but found that the tresses had been stolen. However, the court astrologer, Conon took him to view the stars. There between the constellations Canes Venatici, Bootes, Leo and Virgo was a mass of distant stars, no other than the lovely hair of Berenice spread through the heavens by Zeus himself, displaying its glories for all to see. The king was pleased with this and Berenice overjoyed that Aphrodite had honoured her. The piece is dedicated to the Croatian composer, Ivo Malec (b. 1925), a pupil of Messiaen.

The sixth movement, Jeu des quatre vents (‘Game of the Four Winds’) may seem at first a relatively straightforward impressionistic depiction of the subject matter. But the piece could also be considered as a homage to Debussy with special reference to the Prélude in Book 1, No. VII, Ce qu’a vu le vent d’Ouest (What the west wind saw). Ohana marks his music Animé, tumultueux, commencez un peu au-dessous du mouvement (Animated, tumultuous, begin a little below the tempo), the exact words used by Debussy on the opening pages of his score. But apart from these elements of tribute, Ohana’s music remains entirely his own.

The final piece in the sequence, Aube (Alba) (Dawn), is a meditative expression of a subject popular among composers. The central aspects here are represented by episodes of two part writing, leading in some instances to three voice dissonant chords, which culminate each time in varying patterns of single notes, the exception being the final bars characterised by gentle discords.

Cadran lunaire, written 1981–82, had its première in Rome on 9 December 1982 with Luis Martín Diego, the dedicatee and editor for the work. The title is enigmatic—as Cadran solaire means a sun-dial so Cadran lunaire is ‘moon-dial’, an imaginary device estimating the time by moonlight. The suite of four pieces includes many of the technical innovations and distinctive musical landscapes of Si le jour paraît…, but twenty years on Ohana has refined and intensified his tonal colourings, juxtaposing within each movement a richer variety of contrasts and moods.

The first movement, Saturnal, remembers the ancient Roman winter festival in tribute to Saturn. The central motif of this evocation is a fast and frenzied dance. But between these manifestations of explosive energy, calmer episodes predominate, such as the opening, suggesting moonlight, reflection and meditation on things past.

The title Jondo (profound) is a reference to the art of Spanish flamenco, music of both celebration and lament. This piece is divided into the chordal and the more intricately embellished scalic and arpeggiated elements of Andalusian art. Ohana is not interested in imitating or replicating aspects of flamenco, but in keeping his distance and expressing emotions appropriate to the subject through a somewhat different musical vocabulary once again entirely his own.

Sylva brings us to the landscape of fields and forests often associated with Pan, believed to be the son of Saturn. The recurring motif here is to be found in two-part chords of intervals of fourths and fifths, separated by sharply contrasting devices, including ornamentation, metallic scale runs and varied rhythmic patterns. The two-part chords are at one point rendered with the top voice in harmonics. Towards the end the chords have become three-part in places and are marked as ‘sustained’ and ‘held back’ to evoke an atmosphere of pastoral calm.

Finally the music of Candil, from the Latin candere (to shine or be white hot). This piece initially represents a popular and traditional texture of guitar music, a melody with a bass accompaniment. It is only in the final stages of the work, marked ‘rapid, tumultuous’, that Ohana’s more characteristically dissonant moods return reviving the tensions implicit in the earlier movements.